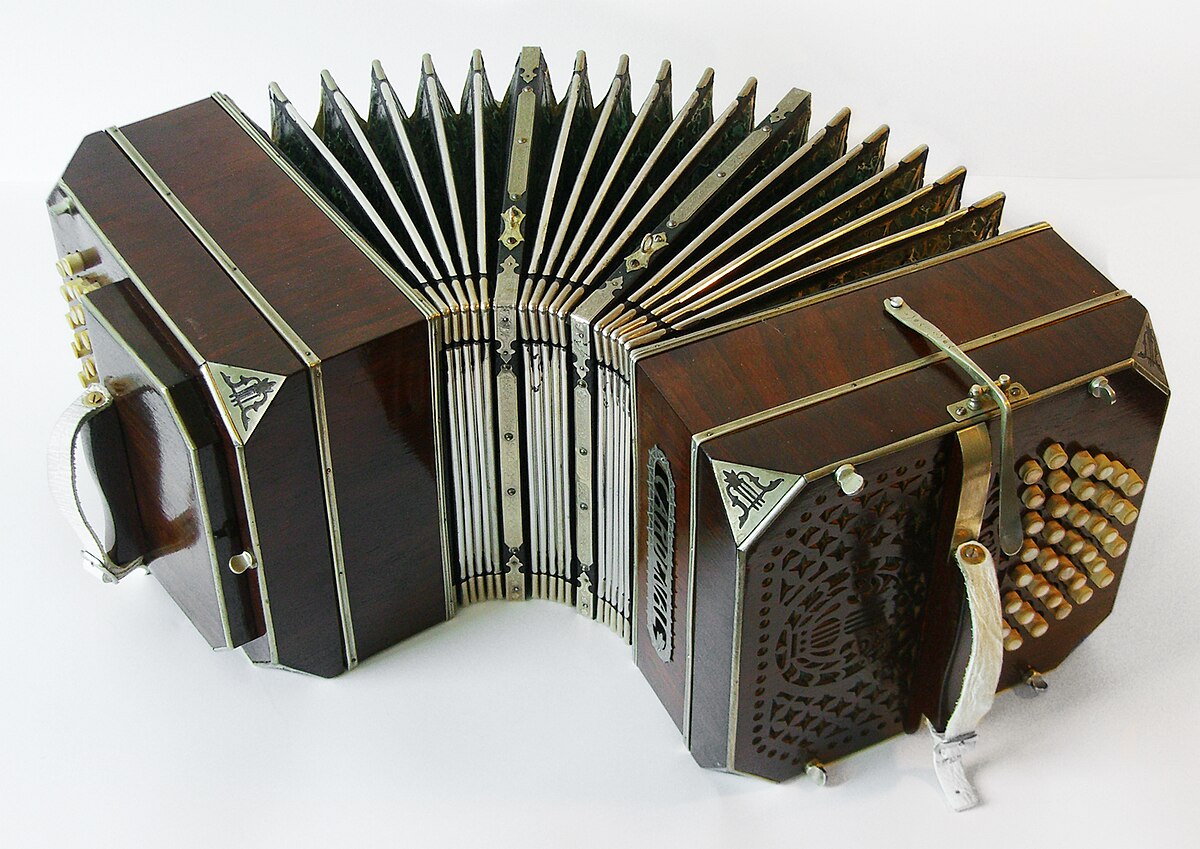

My great-grandfather’s instrument is of a particular kind called the Chemnitzer concertina. Chemnitzers are not only distinct from accordions and other squeezeboxes, they’re also distinct from other kinds of concertinas, so this particular instrument is unfamiliar to most people. I often describe my Chemnitzer simply as “my great-grandfather’s accordion” to avoid needless confusion!

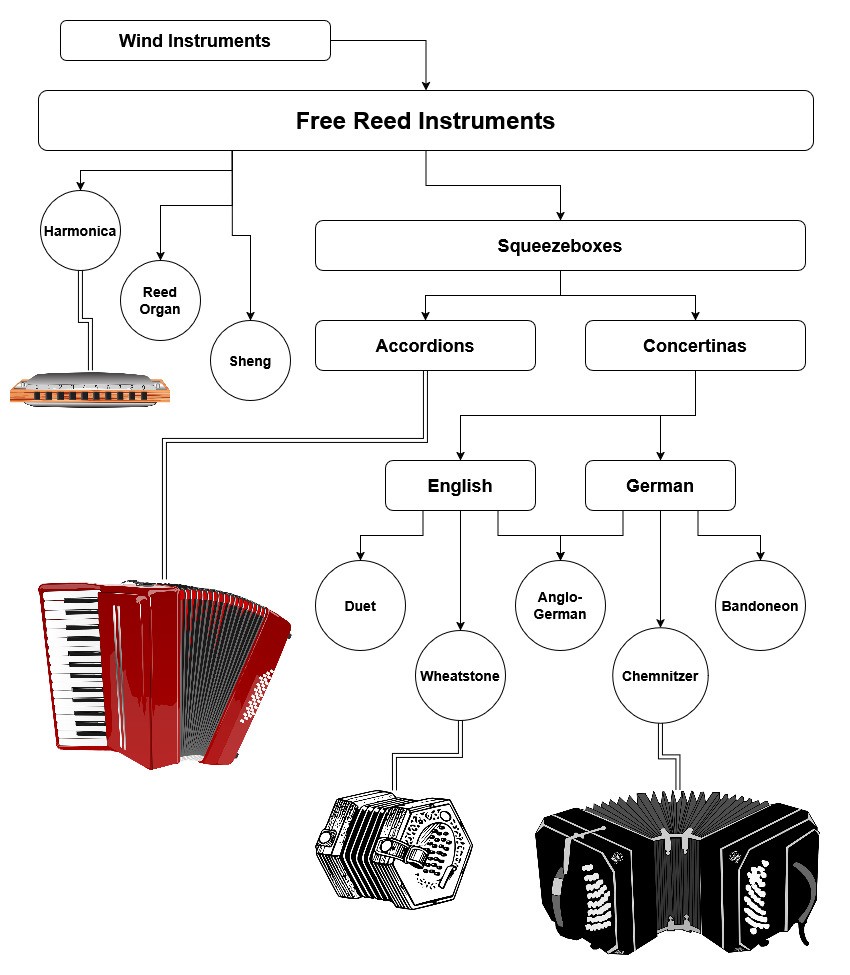

Both concertinas and accordions are types of free reed instruments. Such instruments produce sound by means of a reed affixed by one end in a close-fitting chamber. When air pressure is applied on one end of the reed, the reed is briefly pushed into an open position to allow air to pass, but it quickly swings back due to its rigidity. As pressure continues, the reed swings rapidly back and forth, and its vibration produces a sound whose pitch can be determined by the thickness and length of the reed.1

Free reed instruments were first developed in Asia, most notably the sheng, an ancient Chinese mouth organ dating back to 1100 BCE. When the sheng and other similar instruments became known to Europeans in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, they sparked the creation of many new varieties of instruments using similar free reed designs, including the accordion, reed organ, and harmonica.2

Concertinas emerged in the mid-19th century alongside these other free reed instruments. While concertinas and accordions remain very similar, accordions usually have single buttons that play multiple pitches to form chords, and they tend to have buttons facing forward rather than sideways.

Two men independently developed the first forms of concertinas: Charles Wheatstone’s 1829 design became known as the English concertina,3 while Carl Uhlig’s 1834 design became known as the German concertina.4 Unlike Wheatstone’s smaller, hexagonal design, Uhlig’s square concertina had buttons that each played a different note when pushing versus pulling the bellows. Thus, German concertinas are called diatonic or bisonoric while English concertinas are called chromatic or unisonoric. As concertinas developed over time, other variants emerged, such as the duet, Anglo-German, and bandoneon.5

Squeezeboxes of all kinds quickly became very popular because they could travel easily while producing full harmonic and melodic backing for many styles of music, and because they were cheap to produce.6 Uhlig’s “Chemnitzer” concertina (named after his home city of Chemnitz) was no exception. As he and other manufacturers began shipping and selling the instrument worldwide, they increased the size and added buttons. While the first design had just ten buttons, by the early 20th century, the Chemnitzer most commonly featured 52 buttons in total: 28 on the right side for treble, and 24 on the left for bass. With the bisonoric design, this allowed 104 distinct pitches to be played. Thus, this most common iteration of the Chemnitzer today is called the 104-key Chemnitzer concertina.7

The Chemnitzer concertina became very popular with American immigrants of Eastern European descent in the Great Lakes region. There it became a staple of polka music and was adopted by American performers, musicians, and manufacturers.8

Below I have attempted a rough taxonomy of the Chemnitzer concertina. The image shows how the Chemnitzer relates to other similar instruments like accordion, harmonica, and bandoneon.

Sources and further reading

-

Encyclopedia Brittanica, “Wind instrument”

-

Encyclopedia Brittanica, “Sheng”

-

Neil Wayne, “The Invention and Evolution of the Wheatstone Concertina”

-

Concertina Music, “A Brief History of the Chemnitzer Concertina”

-

Gage Averill, “The Anglo-German Concertina: A Social History (Volumes I and II) by Dan M. Worrall”

-

Jonas Braasch and James Cottingham, “Free Reeds: An Intertwined Tale of Asian and Western Musical Instruments”

-

International Concertina Association, “Concertina History”

-

Ron Emoff, “Accordion in the United States”