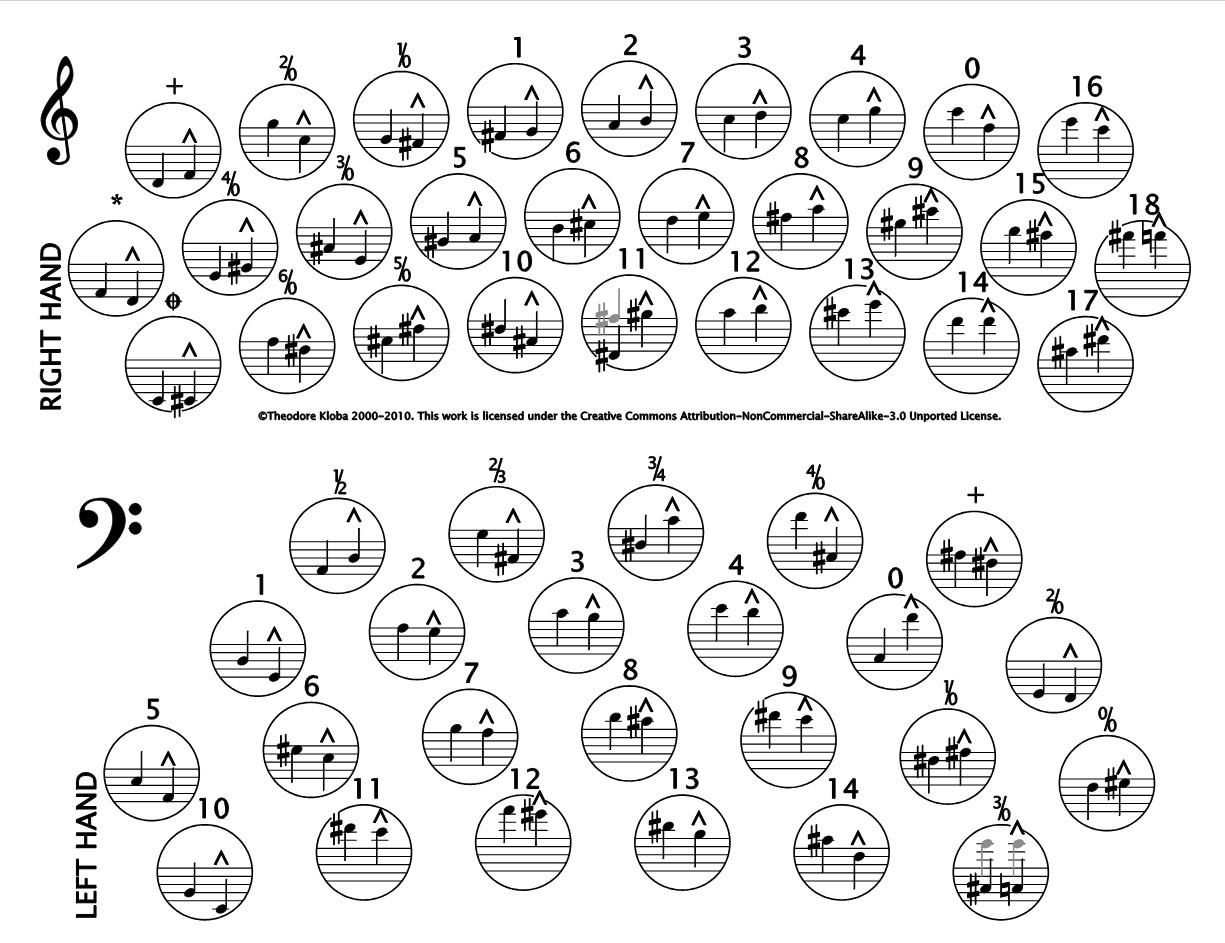

The 104-key Chemnitzer concertina is a rather unique instrument, especially in the layout of its keyboard. When I first sat down with it, I was baffled by the seemingly random note placements. Below I’ve attached an image of a keyboard mapping drawn by Theodore Kloba. I’ve spent many hours staring at this chart as I’ve attempted to learn the instrument!

To read this chart, keep in mind that each button produces a different note on the push versus the pull. Notes marked with a caret are produced on the push, and the unmarked notes to their left are produced on the pull. The markings for each button also appear directly on the Chemnitzer and sheet music for the Chemnitzer (check out some scores from my great-grandfather’s library). Gray notes on the chart indicate note alternatives that occur on newer Chemnitzers – including mine, which dates from 1920s or 30s.

Please view the original post of this resource at the Cicero Concertina Circle website to learn more – and a big thank you to Mr. Kloba for this excellent tool! The chart was made available under CC BY 3.0. If you’re still confused by the layout, this blog post has some helpful tips.

The layout is confusing, but there are some definite patterns. The left hand covers bass (E2-A4) and the right hand covers treble (C4-F#6). On the bass, the closest three rows have some definite chord structure in the lowest notes: the row closest to the performer plays E major on push and B7 on pull, the middle row plays A major on push and E7 on pull, and the second furthest row plays G on push. In the treble, the center of the middle row plays A major on push and E7 on pull, and the furthest row plays G on push and D7 on pull. A few chords fingerings are listed in the table below.

| Chord | Buttons |

|---|---|

| A | 5, 6, 7, 8 (push) |

| E7 | 5, 6, 7, 8 (pull) |

| G | 1, 2, 3, 4 (push) |

| D | 1, 2, 8, 9 (pull) |

| Bm | 10, 7, 8, 9 (pull) |

| Em | 10, 6, 2, 3 (push) |

| F#m | +, 7, 8 (push) |

| B7 | 10, 11, 12, 13 (pull) |

The chords which are most convenient to play and which have the lowest bass notes tend to make for the best arrangements. In my great-grandfather’s sheet music library, only a handful of keys are used, despite the Chemnitzer’s theoretical ability to produce notes and chords in every key. D major is the most prominent key, followed by G major. Minor keys rarely appear in his collection, but I’ve found the instrument is more than capable of supporting rich minor key arrangements.

| Key | # Pieces | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| D major | 98 | 50.0% |

| G major | 61 | 31.1% |

| A major | 18 | 9.2% |

| C major | 12 | 6.1% |

| F major | 2 | 1.0% |

| E minor | 2 | 1.0% |

| A minor | 1 | 0.5% |

| B minor | 1 | 0.5% |

| D minor | 1 | 0.5% |

The Chemnitzer has great potential melodically. It’s capable of producing 49 distinct pitches over a range spanning from E2 to F#6. The majority of these pitches can be played in more than one position – there are only ten notes which can only be played by one button on one bellows direction. These rare notes are mostly focused at the upper and lower extremes of the Chemnitzer’s range, such as E2, F2, D#6, and F#6. Notably, every pitch in the right hand from E4 to D6 appears exactly twice – once on the push and once on the pull. An efficient and practical design after all!

Practically, bellows direction constitutes a serious hurdle for the performer. The whole keyboard layout switches when you change the direction – so your fingers must switch, too! – but air will only last a few bars before running out. The release valve is an important tool for air management. This metal lever positioned at the right thumb allows the performer to open a large separate channel to the bellows and quickly reposition the bellows in either direction. Still, a balance of pushes and pulls is needed, quite comparable to managing bow direction on stringed instruments.

To accomplish balance while maintaining a steady bass accompaniment, all the arrangements I’ve seen maintain one consistent bellows direction for the duration of each chord (which is usually one measure). Perhaps two adjacent chords will both be pushes, but then the third or fourth almost will certainly be a pull. This still requires some good sightreading ability or memory from the performer to switch which keyboard layout (push or pull) is in use – but then again, it also gives a predictable rhythm to this switching!

If you’re setting out to learn Chemnitzer, I’d recommend starting by memorizing some common chords in the left hand and scales in the right hand – mostly ones from D major and G major. Piecing together simple melodies by ear is also a fun exercise. Then, you can learn some simple arrangements like the ones in my great-grandfather’s library. Even complicated arrangements can be stripped down to simpler chords and melody lines.

There’s no doubt – this is a challenging instrument to learn. But with time and persistence it’s very doable! There are also some great resources online. In particular, I recommend Concertina Music’s “Learn to Play” page.

Want the sound and style of the Chemnitzer without the hassle? Try out my free Chemnitzer digital instrument! I mapped all the jumbled notes to a much simpler piano layout that you can play with a MIDI keyboard.